Mole Concept and Avogadro’s Constant

Describe the mole concept

and apply it to substances.

The mole concept applies to all kinds of particles:

atoms, molecules, ions, formula units etc.

The amount of substance is measured in units of moles. The approximate value of Avogadro’s constant

(L), 6.02 x 1023 mol-1, should be known.

A mole (often abbreviated mol) is the

number equal to the number of carbon atoms in exactly 12 grams of pure 12C. Techniques such as mass spectrometry, which

count atoms very precisely, have been used to determine this number as 6.02214

x 1023 (6.02 x 1023 is good enough for IB). This number is called Avogadro’s number to

honor his contributions to chemistry.

One mole of something consists of 6.02 x 1023 units of that

substance. Just as a dozen eggs is 12

eggs, a mole of eggs is 6.02 x 1023 eggs.

The magnitude of the number 6.02 x 1023

is difficult to imagine. To give you

some idea, 1 mole of seconds represents a span of time 4 million times as long

as the earth has already existed, and 1 mole of marbles is enough to cover the

earth to a depth of 50 miles! However,

since atoms are so tiny, a mole of atoms or molecules is a perfectly manageable

quantity to use in a reaction.

The mole is also defined as such that a

sample of a natural element with a mass equal to the element’s atomic mass

expressed in grams contains 1 mole of atoms.

This definition also fixes the relationship between the atomic mass unit

and the gram. Since 6.02 x 1023

atoms of carbon (each with a mass of 12 amu) have a mass of 12 g, then

(6.02

x 1023 atoms)(12 amu/atom)= 12 g

6.02

x 1023 amu=1 g

Calculate the number of

particles and the amount of substance (in moles).

Calculate between the amount of substance (in moles)

and the number of atoms, molecules or formula units.

In order to convert from x moles of

anything to how many actual atoms, multiply x by Avagadro’s constant to find

how many actual particles you have.

For example, say you are given 2.3 moles of

hydrogen. In order to find how many

actual particles of hydrogen you have, you do the following calculations…

2.3

mol H x (6.02 x 1023 particles H/1 mol H) = 1.38 x 1024

1.2 Formulas

Define the term molar mass (M) and calculate

the mass of one mole of a species.

The molar mass of a substance is the mass

in grams of one mole of the compound.

How can we calculate the mass of one mole

of a substance? Let’s take methane for

example. Methane is CH4,

which means in a molecule of methane there is one carbon atom and four hydrogen

atoms. So, the molar mass of CH4

would be, what is the mass in grams of one mole of methane, or what is the mass

of 6.02 x 1023 CH4 molecules? The mass of 1 mole of methane can be found by

summing the masses of carbon and hydrogen.

Mass

of 1 mol C: 12.01 g (This can be found on the periodic table)

Mass

of 4 mol H: 4 x 1.008 g (If you don’t understand where the four came from,

learn what subscripts mean)

Add them.

Mass

of 1 mol CH4: 16.04 g

Traditionally, the term molecular weight

has been used for this quantity. The

molar mass of a known substance is obtained by summing the masses of the

component atoms as we did for methane.

Distinguish between atomic mass, molecular mass

and formula mass.

The term molar mass (in g mol-1) can be

used for all of these.

Molecular

Mass: The mass in grams of one mole of molecules or

formula units of a substance; the same as molar mass.

Formula

Mass: The mass of a formula, including ionic

compounds. Technically, molecular mass

only applies to molecules (which are defined by covalent bonding). Formula mass can also include ionic

compounds, etc.

Atomic

Mass: Atomic mass is somewhat difficult to

define. According to Zumdahl, atomic

mass is technically the average atomic mass of an element, which is determined

by finding the different isotopes of an element present in nature, and how much

percent of the total amount of that element in the world they make up. For example, in nature there are two primary

isotopes of Carbon, 12C and 13C (there are other isotopes

but they are so rare they are insignificant at this level of precision. 98.89% of Carbon is 12C, but 1.11%

is 13C. So to find the atomic

mass of Carbon, we do the following…

(.9889)(12

amu (mass of 12C by definition)) + (.0111)(13.0034 amu (mass of 13C))

= 12.01 amu

This is the atomic mass of carbon.

Define the terms relative molecular mass (Mr)

and relative atomic mass (Ar).

The terms have no units.

The relative atomic mass is the mass of one

atom of an element compared to the mass of Carbon 12. The relative atomic mass has no units because

it is a ratio of masses and the units cancel out. The relative molecular mass is the mass of

the relative atomic masses of all the atoms in a molecule added up. It’s basically the molecular mass without

units as far as I can tell.

State the relationship between the amount of

substance (in moles) and mass, and carry out calculations involving amount of

substances, mass and molar mass.

The relationship between moles and mass is

demonstrated in the mass formula.

Number

of Moles (N)= mass (m)/Molecular Mass (M)…

N=m/M

So, say you are given 40 grams of Carbon

Dioxide, how many moles do you have? The molecular mass of Carbon Dioxide (CO2)

is 44 g. So, the way to solve this would

be to divide 40 grams by 44 g.

Number

of Moles: 40g/44= .91 mol

Note: I am not sure how the units work out for

this. It would appear that the grams

cancel each other out leaving no value, but for some reason you are left with

moles. This may be something to ask your

teacher about.

Define the terms empirical formula and

molecular formula.

The molecular formula is a multiple of the empirical

formula.

The empirical formula is best understood by

knowing its usefulness. One way

scientists find the formulas for molecules is by determining the percent of the

mass each element in the molecule takes up.

For example, let us take CH5N. A scientist is attempting to find the formula

but doesn’t know what it is. He breaks

it up and finds that 38.67% Carbon, 16.22% Hydrogen, and 45.11% Nitrogen. By assuming the compound weighs 100 grams,

each of these percentages now becomes gram units. Then by changing them to moles and setting

them up in ratio to each other, the scientist finds that the ratio of Nitrogen

to Hydrogen to Carbon is 1:5:1. So, he

knows that the formula can be CH5N. However, the formula could also be C2H10N2,

or C3H15N3.

That is because all he has is a ratio.

The empirical formula is CH5N. This is the simplest form. The exact formula is called the molecular

formula, and that will be (CH5N)n where n is an integer. Sometimes the empirical and molecular formula

will be the same, other times they will not be.

If you did not understand the whole percent composition and ratios,

don’t worry, those will be explained later.

The important part is understanding the difference between empirical and

molecular formula and how they are related.

The empirical formula is the formula for the compound that has the

lowest values possible for it to still work.

The molecular formula is the formula with the actual values for the

compound, and it will always be the empirical formula multiplied by some

integer.

Determine the empirical formula and/or the

molecular formula of a given compound.

Determine the:

- Empirical formula from the percentage composition or from other

suitable experimental data.

- Percentage composition from the formula of a compound.

- Molecular formula when given both the empirical formula and the

molar mass.

The steps taken in the previous objective

will be examined in much more detail here.

In order to do these problems we will actually work the problems out,

and taking the same steps with any similar step should work out the same way.

1. Empirical formula from the percentage

composition or from other suitable experimental data.

When a new compound is prepared, one of the

first items of interest is the formula of the compound. This is most often determined by taking a

weighed sample of the compound and either decomposing it into its component

elements or reacting it with oxygen to produce substances such as CO2,

H2O, and N2, which are then collected and weighed. We will see how information of this type can

be used to compute the formula of a compound.

Suppose a substance has been prepared that is composed of carbon,

hydrogen, and nitrogen. When 0.1156 gram

of this compound is reacted with oxygen, 0.1638 gram of carbon dioxide (CO2)

and 0.1676 gram of water (H2O) are collected. Assuming that all the carbon in the compound

is converted to CO2, we can determine the mass of carbon originally

present in the 0.1156-gram sample. To do

this, we must use the fraction (by mass) of carbon in CO2. The molar mass of CO2 is

C: 1

mol x 12.01g/mol=12.01 g

O: 2

mol x 16.00 g/mol=32.00 g

Added

together, the molar mass of CO2 = 44.01 g/mol.

The fraction of carbon present by mass is

Mass

of C/Total mass of CO2 = 12.01 g C/ 44.01 g CO2

This factor can now be used to determine

the mass of carbon in 0.1638 gram of CO2:

0.1638

g CO2 x 12.01 g C/44.01 g CO2 = 0.04470 g C

Remember that this carbon originally came

from the 0.1156-gram sample of unknown compound. Thus the mass percent of carbon in this

compound is

(0.04470

g C/0.1156 g compound) x 100= 38.67% C

The same procedure can be used to find the

mass percent of hydrogen in the unknown compound. We assume that all the hydrogen present in

the original 0.1156 gram of compound was converted to H2O. The molar mass of H2O is 18.02

grams, and the fraction of hydrogen by mass of H2O is

Mass

of H/Mass of H2O = 2.016 g H/18.02 g H2O

Therefore, the mass of hydrogen in 0.1676

gram of H2O is

0.1676

g H2O x (2.016 g H/18.02 g H2O)= 0.01875 g H

And the mass percent of hydrogen in the

compound is

(0.01875

g H/0.1156 g) compound x 100 = 16.22%

The unknown compound contains only carbon,

hydrogen, and nitrogen. So far we have

determined that is is 38.67% carbon and 16.22% hydrogen. The remainder must be nitrogen.

100.00%

- (38.67% + 16.22%) = 45.11% N

We have determined that the compound

contains 38.67% carbon, 16.22% hydrogen, and 45.11% nitrogen. Next we use these data to obtain the

formula. Since the formula of a compound

indicated the numbers of atoms in the compound, we must convert the masses of

the elements to numbers of atoms. The

easiest way to do this is to work with 100.00 grams of the compound in the

present case, 38.67% carbon by mass means 38.67 grams of carbon per 100.00

grams of compound, etc. To determine the

formula, we must calculate the number of carbon atoms in 38.67 grams of carbon,

the number of hydrogen atoms in 16.22 grams of hydrogen, etc. You can do that using the mass formula (found

in 1.2.4.). The answers are 3.220mol C,

16.09 mol H, 3.219 mol N. Thus 100.00

grams of this compound contains 3.220 moles of carbon atoms, 16.09 moles of

hydrogen atoms, and 3.219 moles of nitrogen atoms. We can find the smallest whole number ratio

(empirical formula) of atoms in this compound by dividing each of the mole

values above by the smallest of the three:

C:

3.220/3.219 = 1.000 = 1

H:

16.09/3.219 = 4.998 = 5

N:

3.219/3.219 = 1.000 = 1

So, the empirical formula for the unknown

compound is CH5N. Now, if you

want to know the molecular formula, you have to know the formula mass of the

unknown compound. If the formula mass of

the unknown is the same as the formula mass of the empirical formula, then the

empirical formula is the molecular formula, but if the formula mass of the

unknown is say n times more then the formula mass of the empirical formula,

then the molecular formula is n times the empirical formula.

2.

Percentage composition from the formula of a compound.

Say you are given the formula H2O,

and you want to find out the percentage composition of hydrogen. How you do this is you find the formula mass

of water, and then find the atomic mass of H2, and divide the latter

by the former. Then multiply by 100 to

get a percent value. So, formula mass of

H2O is 18, H2 is 2, so 2 g H2/ 18 g H2O=.11,

x 100=11.1%.

3. Molecular formula given both the empirical

formula and the molar mass.

Say you are given the empirical formula CH5N,

and are told that the molar mass is 62.12 g, and are told to find the molecular

formula. First you find the formula mass

of CH5N, which ends up being 31.06 g. You know that that multiplied by n equals the

molecular mass of the formula you want, and the n in this is case is 2 (you

could find this by dividing 62.12 g unknown/ 31.06 g empirical formula).

Chemical Equations

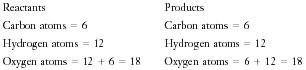

Balance chemical equations when all reactants

and products are given.

Distinguish between coefficients and subscripts.

Say you are given the reaction C6H14

+ O2à CO2 + H2O and

are told to balance it. The main idea

behind balancing an equation is you have to have the same amount of each

element on both sides of the equation, and the only thing you can edit are the

coefficients, not the subscripts. So,

for example, in this equation, in the hexane (reactant), you have 6 carbons,

but in the products you only have one carbon.

So, to balance the carbons you have to place a 6 in front of the

CO2. You now have 6 carbons on both sides. Next look at the hydrogen (a good rule of

thumb is whenever you have an element that is by itself, such as the oxygen in

the reactants, leave it for last). You

have 14 hydrogen on one side and only 2 on the other, so you have to multiply

the water on the right by 7 (because the hydrogen has a subscript of 2, which

means there are two hydrogen in the water compound.) You now have fourteen hydrogen on both

sides. You now move onto the

oxygen. There is 2 oxygen in the reactants

and 19 in the products. There is a rule

when balancing equations that you are not really supposed to use anything but

integers (although when you get into more advanced stuff you will occasionally

use fractions to make it easier on yourself, but you’re not supposed too). So, there is no way to balance it as is. So, you’ll have to go back and change your

original coefficients. If you put a 2 in

front of the hexane and a 12 in front of the carbon dioxide you’ll have

balanced the carbons. Then to balance

the hydrogen put a 14 in front of the water.

Now, you have 28 hydrogen on both sides.

You now have two oxygen in the reactants and 26 in the products. So, by multiplying the oxygen in the

reactants by 13, you have 26 oxygen on both sides and you have balanced the

equation.

2C6H14

+ 13O2à 12CO2

+ 14H2O

In reality, practice makes perfect when it

comes to balancing equations. The only

way to learn is to keep trying, and after a few you’ll get pretty good and fast

at it. Some other rules are that if all

of the coefficients have a common denominator, you can divide everything by

that common denominator (so if the reactants had coefficients of 2 and 4 and

the products had coefficients of 6 and 10, you could divide all of them by

2). And remember that you cannot change

a subscript, and when you multiply a compound by a coefficient the whole

compound is multiplied, not just the front element.

Identify the mole ratios of any two species in

a balanced chemical equation.

Use balanced chemical equations to obtain information

about the amounts of reactants and products.

Using the reaction from above, 2C6H14

+ 13O2à 12CO2

+ 14H2O.

The mole ration from hexane to Oxygen is 2

mol hexane/13 mol O2.

Assuming stoichiometric equilibrium (there are no limiting or excess

reagents) it takes 2 moles of hexane to react with every 13 moles of

oxygen. This can also be done from

reactants to products. Another mole

ratio is 13 mol O2/12 mol CO2. Once again assuming stoichiometric

equilibrium, for every 13 mol O2 you get 12 mol CO2. This can also be done for products and

products (it can be done for any two species in a reaction.)

Apply the state symbols of (s), (l), (g), and

(aq).

Encourage the use of state symbols in chemical

equations.

The state symbols are placed after each

species to specify what state each each species in a reaction is in. The symbol (s) stands for the solid state,

(l) stands for liquid, (g) stands for gaseous, and (aq) stands for in aqueous

solution (dissolved in water). Often

times you don’t have to write the state symbols and they won’t have much

importance, but when they are needed it is really bad to miss them. For that reason I HIGHLY recommend you get

used to using them every time you know what they are, it’ll save you later on

from making the stupid mistake of forgetting them when they are needed.

Mass and Gaseous Volume Relationships in Chemical

Reactions

Calculate stoichiometric quantities and use

these to determine experimental and theoretical yields.

Mass is conserved in all chemical reactions. Given a chemical equation and the mass or

amount (in moles) of one species, calculate the mass or amount of another

species.

The first rule to remember is mass is

always conserved (at least at this point in the syllabus). So the total mass of one side should always

add up on another side. Now, once again

we will use the chemical equation from above.

2C6H14

(g) + 13O2 (g)à 12CO2

(g) + 14H2O (l)

Say you are told that you have 40 grams of

hexane, how many grams of oxygen do you need to completely react with all the

hexane? Well, in order to solve this you

use mole rations.

2

moles hexane/13 moles O2 = 40 g hexane/x moles O2. You then solve this like a normal ratio

problem (multiply diagonally then solve for x).

You answer is 260 grams of oxygen is needed to react with 40 g of

hexane. Note: This is not the best

example because you normally don’t use the measurement grams for gases, but it

would be the same way for liters.

Determine the limiting reactant and the

reactant in excess when quantities of reacting substances are given.

Given a chemical equation and the initial amounts of

two or more reactants:

- Identify the limiting reactant

- Calculate the theoretical yield of a product

- Calculate the amount(s) of the reactant(s) in excess remaining after

the reaction is complete.

1. Identify the limiting reactant.

There are many ways to solve for the

limiting reactant, and everyone tends to like their own way. I will show mine below but if you don’t like

it feel free to ask your teacher or someone else for another way to do it. Say you have the equation

4FeCr2O4(s)

+ 8K2CO3(s) + 7O2(g) à 8K2CrO4(s) + 2Fe2O3(s) +

8CO2(g)

The

masses are 169 kg, 298 kg, and 75 kg respectively for the reactants, and you

want to find out which one is the limiting reagent. In order to do this, you first have to find

out how many moles of each of the reactants you have (using the mass formula),

we find their to be 7.55 x 102 mol chromite ore, 2.16 x 103

mol potassium hydroxide, and 2.34 x 103 mol O2.

You then set up the mole ratios you need to

react correctly and the mole ratios you have.

So,

to react correctly you should 4 moles of chromite ore for every 8 moles of

potassium carbonate. That is, 4 mol FeCr2O4/8

mol K2CO3(s), which equals .5. You then take the values that you actually

have, which are 7.55 x 102 mol chromite ore/2.16 x 103

mol potassium hydroxide, which equals .35.

This is smaller then .5, and that means that the numerator is too small

(if the answer was bigger then .5, the denominator would be too small). Whichever value is too small, that number is

the limiting reagent FOR THAT PAIR. You

then have to take that reagent and compare it with the other reactant, or the

rest of the reactants if there are more then three. So, taking chromite ore we do the same thing

comparing it with oxygen. We have 7.55 x

102 mol chromite ore/ 2.34 x 103 mol O2 which

then equals .32. The ratio we want is

4/7, or .57, which is bigger then the actual value we got, which means O2

is the limiting reagent of the entire reaction (you don’t have to then compare

it to the first reactant tested). So,

oxygen is the limiting reagent of the formula.

2 and

3. Calculate the theoretical yield of a

product and amount of excess reagent remaining after reaction is complete.

Theoretical yield of a product is the

amount of a product formed when the limiting reactant is completely

consumed. In order to obtain it, you go

through several steps, that we will go through with the reaction 2C2H6

+ 7O2 à 4CO2

+ 6H20 starting with 20 g of ethane and 40 grams of oxygen. So, the first step is to identify the

limiting reagent.

2

mol ethane/7 mol oxygen=.29 .66 mol

ethane/1.25 mol oxygen=.528. Since the

number is too big, that means the denominator is the limiting reagent, or

oxygen is the limiting reagent. We then

have to find how much ethane is used up before the oxygen is consumed. We do this by multiplying the actual amount

of oxygen by the mole ratio of the two reactants.

1.25

mol oxygen x (2 mol ethane/ 7 mol oxygen)= .36 mol ethane.

This is how much ethane is used up in the

reaction, so now we know how much ethane was used and we know how much ethane

we started with, so to find how much ethane is left over we do a simple

subtraction.

.66

mol ethane started with - .36 mol ethane used = .3 mol ethane left over.

So, we have .3 mol ethane left over after

the reaction. Then, to find theoretical

yield, you have two options. You can

use how much oxygen use, or you can use how much ethane you use in the

reaction, either should gain you the right answer. I would recommend using the value given to

you by the problem, so that way if you made a mistake in finding the excess

reagent left over you won’t mess up your second answer. You know you used 1.25 mol oxygen, so you do

another mole ratio.

1.25

mol oxygen x (4 mol carbon dioxide/7 mol oxygen)=.714 mol carbon dioxide.

So, .714 mol carbon dioxide is your

theoretical yield for that product.

Note:

Rarely do you ever calculate the theoretical yield, because side reactions

normally occur that decrease from the theoretical yield. The actual yield is sometimes compared to the

actual yield by doing the following calculations: actual yield/theoretical

yield x 100= Percent Yield.

Apply Avagadro’s law to calculate reacting

volumes of gases.

Avagadro’s law is V=an, where V stands for

volume, a stands for proportionality constant, and n is the number of moles of

gas particles. Basically, what this

equation states is that for constant temperature and pressure, the volume is

directly proportional to the number of moles of gas. This relationship is obeyed closely by gases

at low pressures. An example of this can

be exemplified by the following reaction 3O2(g) à 2O3(g) . The

temperature and pressure of this reaction are constant (25 degrees C and 1

atm). Say we start with a 12.2-L sample

containing 0.50 mol oxygen gas. What

would be the volume of the ozone?

0.50

mol oxygen x 2 mol ozone/3 mol oxygen= 0.33 mol ozone.

Avagadro’s law can be rearranged to show

V/n=a. Since as is a constant, an

alternative representation is V1/n1= a =V2/n2

So, for this reaction n1 equals

0.50 mol, V1 equals 12.2 L, n2=0.33 mol, and V2=? By setting up the above rearrangement of

avagadro’s law, 12.2/0.5=?/0.33, so the volume is 8.052 L.

Solutions

Define the terms solute, solvent, solution and

concentration (g dm-3 and mol dm-3).

Concentration in mol dm-3 is often

represented by square brackets around the substance under consideration, eg.

[CH3COOH].

Solute:

A substance dissolved in a liquid to form a solution.

Solvent:

The dissolving medium in a solution.

Molarity:

moles of solute per volume of solution in

liters. This often times written by IB

with units mol dm-3, which means moles/dm3, and a dm3

equals a liter. Same meaning, just

different ways of writing it. I recommend

writing it mol dm-3 whenever your in IB class because it gets you

well practiced, but if you are working with people outside of the IB program

write it per liters, because I have found they have a hard time understanding

IB notation. This is also often times

written short hand in square brackets such as [CH3COOH]. That means the molarity of that

compound. This could also be written as

g dm-3,(molality) however I have never seen it written that way,

even by IB. If it is ever written that

way, I would recommend converting it to moles (by just using Avagadro’s

number), however I could see how having it in grams may help calculate it at

some point. So, if you dissolve 5 moles

of HCl in 3 Liters of water, your molarity [HCl] is 5 mol/3 L, or 1.66 mol L-1,

or 1.66 mol dm-3.

Carry out calculations involving concentration, amount of solute and volume of

solution.

These are fairly easy. Just remember that concentration equals

amount of solute/volume of solution. So

say you know the concentration of a solution is 4 mol dm-3, and you know the

volume is 5 L. That means x mol/ 5 L=5

mol/L. That means x must equal 20 mol.

Note: A good rule to remember is the equation m1L1=m2L2. m stands for the molarity, and L stands for

volume. So, if you had a 2 L

concentration of 5 M HCl solution (M is often used to stand for molarity) and

you wanted to dilute it to a 2 M HCl, how much water would you need to

add? Well, m1=5, L1=2, m2=2, and L2=?. So, (5 mol/L)(2 L)=(2 mol/L)(? L). By solving for the unknown, you find your

final solution will be a volume of 5 liters, and since you started with 2

liters, you need to add 3 liters to get to 5 liters.

Solve solution stoichiometry problems.

Given the quantity of one species in a chemical

reaction in solution (in grams, moles or in terms of concentration), determine

the quantity of another species.

When it is given to you in grams or moles,

it’s just like a regular stoichiometric problem. However, if it is given to you in terms of

concentration, work your way around it to find moles or grams (so, if you have

a concentration of 5 M, then you have 5 moles per liter, and if you have 3

liters, that means you have 15 moles.)